"

This is where I plan to share my thoughts on interesting stories and articles I find across the internet. There will be posts about technology, psychology, photography, and whatever I come across.

Some of you may be following the development of the forthcoming fifth revision to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the major book used for psychiatric diagnosis. There has been a lot of criticism due to the secrecy of the process this time around, but the British Psychological Society (BPS), the major mental health organization in the UK, is taking an even more interesting and refreshing angle: criticizing the entire current framework of diagnosis.

The DSM takes a medical approach to diagnosis. In short, this means that a ‘patient’ is assumed to have an underlying ‘pathology’ that manifests as various ‘symptoms’ that are assessed to make a ‘diagnosis’ and then apply a ‘treatment’ to said diagnosis. This approach basically makes various human conditions into ‘illnesses’ that need ‘interventions’ like medication or cognitive behavioral therapy. In a recent paper, BPS has criticized this framework as harmful to individuals and the public.

“The Society is concerned that clients and the general public are negatively affected by the continued and continuous medicalisation of their natural and normal responses to their experiences; responses which undoubtedly have distressing consequences which demand helping responses, but which do not reflect illnesses so much as normal individual variation. (p.1)”

“We believe that classifying these problems as ‘illnesses’ misses the relational context of problems and the undeniable social causation of many such problems. For psychologists, our well-being and mental health stem from our frameworks of understanding of the world, frameworks which are themselves the product of the experiences and learning through our lives. (p.4)”

As a practicing psychologist who also teaches a class on diagnosis for master’s level therapists, I could not be more excited reading this paper. BPS essentially takes a more humanistic and social constructivist approach to the problems of living. The benefits of this include reducing stigma, a larger focus on the interpersonal dimensions of mental health, and normalizing the experience of having problems during life. Cheers to you BPS, now if only your American counterparts would get the message…

Dr Will Meek is a psychologist practicing in Vancouver, WA. He writes regularly about mental health on his blog: Vancouver Psychologist

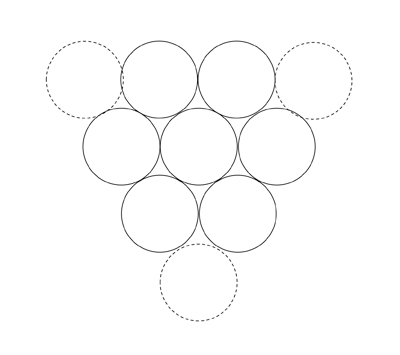

Did you solve it? Any other answers?

Did you solve it? Any other answers?

I could end the deficit in 5 minutes. You just pass a law that says that anytime there is a deficit of more than 3% of GDP all sitting members of congress are ineligible for reelection.

This calls for a drink.

View"

Editor’s note: This guest post is written by Tom Anderson, the former President, founder and first friend on MySpace. It is adapted from a comment he made on Google+ and reprinted with permission. You can now find Tom on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+

Today at the Facebook news conference, a reporter asked Mark Zuckerberg what he thought of Google+. Zuckerberg responded by saying that lots of companies are going to build things like video chat, but Facebook competitors also have to build up their social graph first. Facebook’s job is to just keep innovating. It’s a perfectly reasonable response, and of course, he’s exactly right—the challenge is to get the user base, and make it easy for them to use your product. Done and done for Facebook. The integration looks great.

Some pundits are complaining that the technology is not new, but that’s besides the point. Case in point: at MySpace we launched what Zuckerberg is announcing in 2007 (try googling “myspace skype partnership”), and MySpace also had one-on-one video chat back in 2004. The point is that people weren’t really ready for it back then—now is the time, and Facebook has the user base. The large user base (750 million) paired with a simple integration of arguably the best voice/video tech (Skype) is what makes this news.

Zuckerberg also pointed out in his response to the Hangout question, that one-on-one video chat will be the more common use case (Google+ has “Hangout” which allows 10 users to video chat at once). Again, perfectly reasonable, and probably right. Many sites have group video chat, Google+ is not the first, nor is Hangout a game-changer. What you need here is the user base, which currently only Facebook has, and people will more likely talk one on one (like we do on the phone, duh).

The more interesting part of his announcement, I think, was the implicit response to Google+ in his intro leading up to the Skype integration. What Zuckerberg said is that Groups on Facebook are actively used by half of the 750 million user base. And “Groups” is really Facebook’s second attempt at “Friends Lists,” which Zuckerberg admitted last year, was not getting traction (people didn’t want to do the work of putting people into lists).

The Facebook Groups feature is designed in a way so that users who do care to do the work, can. Someone invites you, and you’re in the group without you having to take any action. (In fact, you have to do some work to get out of the Group!) Zuckerberg points out that this is how friend requests work as well—there’s always a select few who do all the friending, and the rest of us just follow along, with a much easier “approval.” Facebook’s Groups were designed in a way to overcome the friend list problem. They’ve grown quickly, even if 95% of the user base can’t be bothered to make their own groups.

And if you think about it, that’s the smart way Facebook has approached many things: build an app platform, and let the developer community do the heavy lifting. Create a translation platform, and let users translate Facebook in every language known to man. Create a Group feature, and let the 5% create the groups for the other 95%. It’s like Mechanical Turk, but we’re not getting paid. (Unless you’re Zynga!)

What remains to be seen, is which model will users prefer in the long run—Facebook “Groups”—which function more like an old-school Yahoo Group with a Forum built-in). Or Google+ “Circles”—which is more like an email distribution list meets Twitter with better commenting. The two are actually very similar, but each probably does certain things better than the other. Thinking about what each model does better is probably the key to unlocking what “model” is going to “win.”

Even as Facebook revealed some new chat products on Wednesday, the elephant in the room was Google’s latest attempt to create a social network, Google+. Mark Zuckerberg tried deflect direct comparisons by saying, “Every app is going to be social.”

But he did make one remark, which suggested how he really feels about Google+ and one of its main features, Circles. Zuckerberg didn’t mention Circles specifically but he did state:

The definition of groups is . . . everyone inside the group knows who else is in the group

This might seem obvious unless you’ve played with Circles. The Circles feature is how Google+ handles groups, but it is not completely intuitive and problems can arise when different Circles collide It is designed to let members set up different groups of people, or Circles, to share things with.

But Circles are one-way, or asymmetric. Everyone sets up their own Circles and nobody knows whose Circle they are in. Secret Circles would be a more apt description. Zuckerberg seems to be suggesting that they are not really groups because instead of everyone in the group knowing who else is in the group, it is the exact opposite: nobody knows which groups they are in.

Circles are so confusing that Ross Mayfield created the Slideshare below to explain it all. Facebook has a “symmetric sharing” model where two people mutually confirm that they are friends, and then can start sharing stuf with each other privately or publicly. Twitter has an “asymmetric follow” model where people Tweet out publicly and anyone can follow what they are broadcasting without that person necessarily following back. It’s one-way.

Google+, however, has an “asymmetric sharing” model where you can share one-way with people, but they don’t have to share back. It’s kind of like the Circle of Trust in Meet the Fockers (watch the video clip in the third slide), only not quite as funny.